The violence in Iraq has been remarkably concentrated; 48% of the civilian deaths since 2003 have been in and around Baghdad (Image: The Times, Philippe Naughton)

The internecine conflict that tore through Iraq in 2006-2008 may rekindle in the near future; the inflaming of sectarian tensions is a possibility. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki has centralized power in his own hands; the judiciary in Iraq has been weak and politicized, civilian and political opponents have been intimidated, and the use of torture by government interrogators has not been uncommon. Is there a way to ensure peace and security for Iraqis while at the same time restricting the power of Maliki? The issue of decentralization, which would involve a restructuring of federal relations, must be discussed as a viable solution to Iraq’s problems. How could the restructuring of Iraqi federal relations contribute to resolving sectarian tensions?

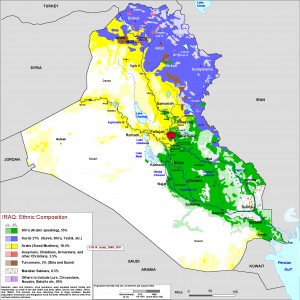

Before tackling that larger issue we must ask: What are the sources of sectarianism in Iraq? One possible source is Iraq’s heterogeneous character. By heterogeneous, I mean that within Iraq’s borders there are multiple group identities that appear to be antagonistic and exclusionary. What is the make-up of Iraqi society? And why do I suggest that such identities appear to be antagonistic and exclusionary? Regarding the make-up of Iraqi society, the majority of Iraqis (roughly 75% of the population) are Arab. The Kurds are the largest ethnic minority, comprising 15-20% of the population. The Kurds speak their own distinct language and are dominant in the northern and mountainous region of Iraq, known as Kurdistan. Other minorities— Turkomen and Assyrians—make up roughly 5% of the population and are interspersed throughout the country. Overwhelmingly, the people of Iraq are Muslim, with 97% of the population practicing some form of Islam. Around 60% are Shi’a, while roughly 30% are Sunnis. Christians and other religious groups represent 3% of the population.

Regarding my contention that there are multiple group identities that appear to be antagonistic and exclusionary, it is useful to begin with a definition of “social identity.” This is an individual’s conceptualization of himself or herself based on a perceived membership in a group. I refer to “social identity” as “group identity” for the remainder of the paper. At first glance, a group identity would appear to be necessarily relative and malleable. When I leave the city of Ottawa to go to Toronto, I identify as being a resident of the former. When I go to a sports bar I identify with a particular soccer team. And when I travel internationally I identify as a Canadian. So, an individual holds multiple group identities. What makes a society heterogeneous is not merely the existence of multiple group identities but the multitude of certain types of group identities. While relations between members of two soccer teams might be competitive—even antagonistic—presumably, anyone can gain membership to a soccer team’s fan base. Yet some group identities are exclusionary as people the world over perceive others as having certain identities that are fixed from birth; a person is either a Tutsi or a Hutu; an Anglophone or Francophone; black or white. In the case of conflict between Irish Catholics and Protestants, while a person could theoretically be baptized to become a Catholic or a Protestant, there is still a perception that such identities are about race, in which case they are fixed from birth.

Literature on conflict resolution confirms that group identities, while socially constructed, can reach a point where they are essentially fixed. Put differently, an individual’s identification with a particular group intensifies during or after a conflict to the point that negative perceptions are engrained in the minds of individuals; these perceptions, or “enemy images” as Janice Stein calls them, are difficult to reverse. That group identities can be exclusionary and antagonistic has been made abundantly clear by events in Iraq. Abu Mustapha, an Iraqi bureaucrat, describes the unsettling change in identities among Iraqis following the 2003 invasion:

…people began changing offices. The remaining Sunnis all put their offices in certain halls, and Shi’ites did the same in others. No one would ever have thought of doing this at the ministry in the old regime. We were all just colleagues at the Ministry of Agriculture. None of us cared who was Sunni or Shi’ite before.

In a situation of uncertainty or insecurity—such as the breakdown of state authority—an individual will more closely associate with some identities than with others, often to the point of exclusion. This is because in such situations, an individual might have a particular identity imposed on them by another group. If individuals of a particular group are facing persecution, they might join together to protect themselves and their kin; thus a security dilemma fuels ethnic hatreds in intrastate conflict. Iraqi society would appear to be no exception.

Iraq’s ethnic composition (Source Gulf 2000 project, Columbia University, NYC)

The violence in Iraq has been remarkably concentrated; 48% of the civilian deaths since 2003 have been in and around Baghdad, with other deeply-troubled areas being the province of Diyala, the province of Salah al-Din and the province of Anbar. The latter province was an “epicentre” of the insurgency that emerged after the invasion, and its city of Fallujah is a case-in-point for understanding the ethnic cleansing as well as the formation of exclusionary and antagonistic group identities. After the Coalition assault on the city of Fallujah in 2004, hundreds of thousands of refugees took flight, many of them settling in areas of Western Baghdad. Shia residents of these areas were forced out by newly-arrived refugees, some of whom had been radicalized by their experiences in Fallujah[1] and organizations such as Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia conducted attacks in Shia neighborhoods. As predicted by the literature on conflict resolution, individuals began seeking security with militia groups that corresponded to their religious or ethnic identity; enemy images became ingrained, and a tit-for-tat pattern emerged between insurgent groups. For example, when a bomb destroyed the Shi’ite Al-Askari Mosque in the Salah al-Din province, a wave of violence erupted across the area against Sunnis Muslims. Finally, individuals sought security in sectarian-aligned groups such as the Mahdi Army and the Sadrist movement, both under the leadership of radical Shi’ite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. Not unlike Hezbollah, the Sadrist movement created networks of charities to distribute food and supplies to ordinary Shi’a Iraqis while at the same time acting as a source of radicalization.[2]

So, Iraqi society would appear to be marked by multiple and exclusionary ethic and group identities. Iraq would also appear to be a multinational society. By “nation,” I mean the “imagined community” as described by Benedict Anderson. Since face-to-face interaction is impossible in highly-populated societies, members imagine each other as having a common language, history, and value system. As Anderson writes: a nation “is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion”. Some scholars and policy-makers have argued that there is a weak, if not non-existent, perception of an Iraqi nation. Leslie Gelb of the Council on Foreign Relations argues that the state of Iraq was “cobbled” together and that a three-state partition is a solution. Similarly, historian Margaret MacMillan writes that the creation of the Iraqi state “threw peoples together”. The implication here is that Iraq is an artificial state and must be partitioned. But such views are unsatisfactory and as Sherko Kirmanj writes, Iraqi identity existed before the creation of the Iraqi state. Specifically, there was a notion of an “Iraq” before the creation of the state as scholars and travellers in the 19th century referred to the geographical area as such.

Without a doubt, ethnic, religious and national identities matter. The violence of post-2003 occurred along the fault-lines of antagonistic and exclusionary group identities. Nevertheless, the heterogeneous character of Iraq is in fact insufficient to explain sectarianism. Up to 70% of Iraqis support the idea of a unified Iraq. Additionally, James Fearon and David D Laitin find no statistical support for the argument that one can predict the likelihood of intrastate conflict based on how heterogeneous a society is. Finally, the existence of stable, heterogeneous societies—such as Belgium, Canada or Switzerland—while having multiple exclusionary group identities within their borders nevertheless have a widely accepted national identity which trumps other identities. True, Canada and Belgium have both have strong separatist elements within their borders. But such societies have managed to remain stable and prosperous while allowing the flourishing of diversity. In short, Iraqi society was by no means doomed by its heterogeneous character to descend into the sectarian chaos of 2006-2008. We must look further to explain sectarianism in Iraq.

In future posts, I will examine the history of Iraq from 1920 to 2003, I will describe the weakness of the Iraqi state and how that weakness was made worse by decisions of the Coalitional Provisional Authority, and I will describe the exclusionary regime practices that have contributed to sectarianism.

[1] Toby Dodge, Iraq: From War to New Authoritarianism: 57

[2] Michael R Gordon and Bernard E Trainor, The Endgame: The Inside Story of the Struggle for Iraq, From George W Bush to Barack Obama, (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012)

Also by Matthew

Could restructuring the federal relations in Iraq create a lasting peace?

Could restructuring the federal relations in Iraq create a lasting peace?

The capacity of the Iraqi state is still tenuous and the sectarian tensions that embroiled the country after the invasion could re-emerge. Long-term stability for Iraq will require resolving disputes over federal relations.

Related articles in the categories Middle East and North Africa and Religion

Trackbacks / Pings