Nearly three years of conflict in Syria calls for some reflection. As the Arab Spring reached Syria, Syrians took to the streets to protest President Bashar Al-Assad’s regime. Popular protests soon turned into a bloody tug of war between forces loyal to Assad and rebels. To the outside world, the full-scale civil war tends to bring attention to the human suffering – more than 130,000 deaths and over 6 million refugees and displaced persons – and the conflict itself. But one silent aspect of war that slowly erodes human identity is going relatively unnoticed – the destruction of cultural heritage.

Syria is home to six UNESCO World Heritage Sites. These sites are situated in Damascus, Aleppo, Palmyra, Bosra, the Crac des Chevaliers and Saladin’s Castle, and the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria. Beyond the facade is over two thousand years of history where many civilizations crossed paths, thrived and fell. The architecture speaks to the legacy of these rich civilizations, preventing them from fading into history. Bronze Age civilizations including the Babylonians, the Assyrians and the Hittites left their mark. Thereafter, the Greeks, the Persians, the Romans and the Arabs placed their epicentre in Syria. In more recent history, the European Crusaders constructed magnificent castles; and the Ottoman Empire also contributed to this legacy. Syrian architecture is a testament to its rich and complex cultural heritage that forms the bastion of collective memory.

Now that Syria’s cultural heritage is under fire, many may render it secondary to traditional security. Through a state-centric lens, those ascribing to traditional security focus on the military, conflict and survival of the state. Emerging security challenges have expanded to encompass human security, environment security and energy security, questioning the concept of security in the process. Based on rationalist assumptions, many security scholars still attribute states’ ‘irrational or dysfunctional behaviour’ to culture. This narrow scope of culture, however, limits our understanding of the interplay between security and culture.

As Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann contend: ‘Reality does not exist out there waiting to be discovered; instead, historically produced and culturally bound knowledge enables individuals to construct and give meaning to reality.’ Culture constructs a cognitive lens that infuses meaning in everything, from symbols, rules, and concepts to buildings, passing on narratives to successive generations.

The Triad: Heritage, Memory and Identity

Falling within culture is architectural destruction and its inextricable ties with heritage, memory and identity. In The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, Robert Bevan argues that architecture became ‘a weapon of war’ rather than something that ‘gets in the way of its smooth conduct’ in the twentieth century. For this reason, it was not merely a war tactic required for carrying out military operations or collateral damage. Due to the symbolic meaning attached to architecture, it became a deliberate target. Architecture, in depicting cultural heritage, becomes engrained in the memory of a group as an integral part of identity.

A deliberate attack on architecture is aimed at achieving political ends that erase any evidence of the other group’s existence. Genocide is often accompanied with what is termed cultural genocide. As Czech historian Milan Hubl asserts: ‘The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history.’ Pulverizing architecture becomes a tool for erasing memory, distancing the group from the site. It lays the groundwork for inventing a new history, as a group’s sense of belonging to a community becomes buried underneath rubble.

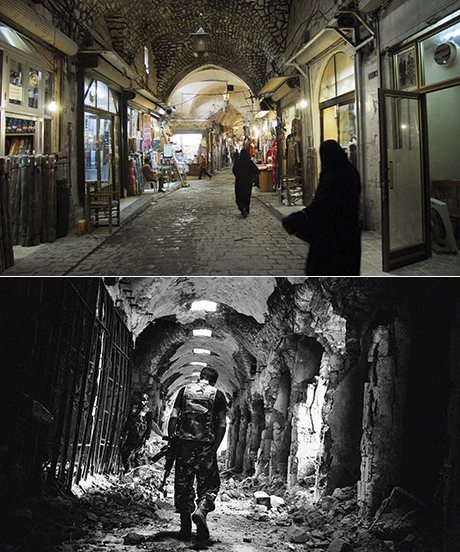

The Old Souk, Aleppo. Above in 2007 and below in 2013. Photographs: Corbis, Stanley Greene/Noor/Eyevine

Throughout history, architecture becomes a site to express an act that is not devoid of significance for both groups. Israel’s demolition of Arab villages attempted to cut ties between a group and its unique architecture. More destructive acts – Turkey’s eradication of Armenian architecture after their genocide and Nazis’ attack on Jewish architecture prior to the holocaust – aim to completely erase the existence of a certain group by targeting cultural heritage. Over time, these acts ‘liquidate a people’ as they may no longer associate with the site and even forget what is was. Terror is another reason for attacking architecture that was evident during World War II when Nazi Germany bombed London, Coventry and Canterbury; and the Allies responded by bombing historic German cities. Today, the destruction of Syria’s ancient treasure presents architecture as a site replete with symbolic meaning for Syrians and arguably, universal heritage in general.

Syria: Loss of Ancient Treasures

Ancient treasures in Syria including crusader castles, churches, mosques and even antiquities are on the verge of loss. It mirrors the destruction caused following the aftermath of Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003. In the midst of anarchic environment, the destruction of cultural heritage– the looting of the national museum, the burning of the Koranic library and the wiping out of ancient Sumerian city – was partially attributed to inadequate effort to protect architecture in war. Perhaps it came as an afterthought in a state usurped by violence and chaos.

Now Syria’s fate is at the crossroads of security and culture. The infighting between government militia and rebels has transformed the ‘Dead Cities’ of the north, along with other historical sites, into a battlefield. Achieving political ends, no matter the cost, has led to history being obliterated into mere rubble and debris. Crac des Chevaliers is exemplary of the destruction wrought by being caught in the midst of this tug of war. Emma Cunliffe’s illuminating account of damage on the archaeological sites discusses ‘shells and exchanges of fire in the castle itself’ and the surrounding areas. Rebels who sought refuge in crusader castles of Crac de Chevaliers and Shayzar thinking they would be safe, found that the Syrian army would not be reluctant to destroy historic buildings. Due to the volatile political landscape, many sites have been exposed to bombing, shelling, fire and looting.

Souq Bab Antakya, Aleppo. Above in 2009 and below after an attack in 2012. (Photographs: Alamy, Reuters)

Crac de Chevaliers’ history may propel its cultural importance towards the eyes of the international community. Whilst it was originally an Arabic castle, it was renowned as the headquarters of the Knights Hospitaller. This military castle’s construction and changes are reflective of waxing and waning of civilizations, even if it is more closely linked with the legacy of Crusades. The ‘dead cities’ constituting hundreds of Roman-Graeco towns outside Aleppo and Umayyad Mosque in Deraa, one of the oldest Islamic-era structures, have become damaged as fighting envelopes Syria. Therefore, the apparent indiscriminate nature of damage and looting of artefacts is not equivalent to a deliberate attack on architecture that effaces history.

Sadly, it brings to the fore another truth about war – the cacophony of war weapons and yet the echoes of silence at these sites. Whether it is the rebels or Syrian Army, the heavy fighting persists to achieve political ends, eroding cultural heritage of both groups. Ironically, war and its damage often becomes part of a city’s fabric and identity that unites one group against others. Yet the annihilation of architecture on a massive scale deprives a certain group of its cultural heritage. Human suffering also raises ethical questions on prioritizing human life over lifeless buildings. Protecting cultural heritage, however, is part of preserving a population’s sense of what makes them unique. For Syria, a site where many civilizations crossed paths, its narrative is of universal value. Architecture – unwinding as a space replete with profound meaning – speaks more eloquently than ever imaginable.

Find more articles by Zoufishan here.

Related articles in the categories Culture and Identity, Middle East and North Africa, Syria, Warfare.

Trackbacks / Pings