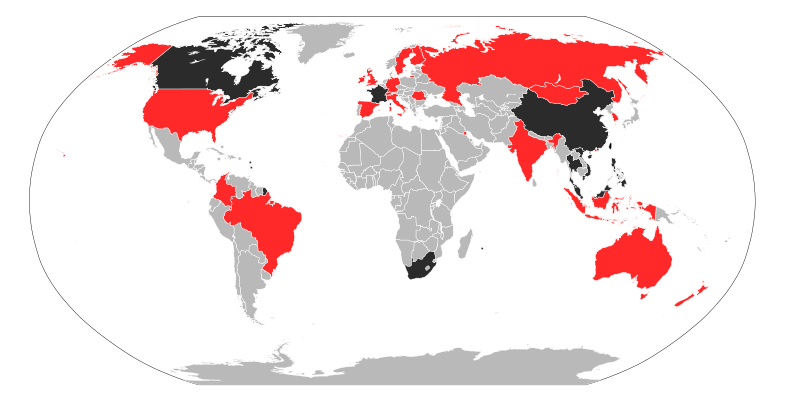

A pandemic nearly always guarantees a big headline as it leaves us wondering where we went disastrously wrong in our perceptions. The 2004 SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak that caused panic all across East Asia and much of the west, more than most disease-related events of the early twenty first century, awoke the general public to the dangers of unmonitored infections.

The week of February 10, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry along with Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of Health and Human Services, and Lisa Monaco, assistant to the President for homeland security and counterterrorism, made an official statement regarding the government’s new agenda for global health security. The message attempted to reassure the public that with strengthened surveillance that an episode like the 2001 anthrax attacks or the 2009 flu pandemic won’t happen again. This is not the first time that the government has had to address growing concerns of bioterrorism and dangerous infectious diseases encroaching into the tranquility of American life, but it’s the first time that they’ve felt the need to make it official, with a new task force, rather straightforwardly titled, the Global Health Security Agenda, designed to target emerging pathogens and bioterrorist threats before they hit U.S. shores.

The major health branches of the U.S. government, which includes the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Washington, D.C., are at the frontline of breaking news related to outbreaks, yet the government hasn’t until now outlined a clear-cut mission statement on preparedness. In continuing to keep in step with international monitoring agencies like The World Health Organization and the United Nations, the U.S. hopes to send a strong message in communicating their focused ambitions in the field of global health.

The urgency to tackle future outbreaks on U.S. shores has a good deal to do with our current unprecedented surge in air travel. An airplane, in in of itself, is self-contained metal incubator of diseases. Imagine a boarding a flight from Hong Kong to Los Angeles, or Moscow to New York, where one passenger may be coughing incessantly with an undetected form of avian influenza or even tuberculosis. The recycled air, low humidity, and pressurized compaction of passengers makes the plane environment a natural breeding vessel for pathogens.

In 2007, the case of an American man with extreme multidrug resistant tuberculosis (which he picked up while living in Russia) who had defied quarantine orders and went out and about potentially threatening to infect others, caused a stir among otherwise complacent Americans who felt that the disease was a throwback to the nineteenth century. The threats of SARS and avian influenza aside, the new fears relating to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, which has already killed 60 in Saudi Arabia and threatens to spread from the Middle East to the West is a cause of some alarm to U.S. authorities.

This is nothing to say of the enormous economic burden caused by pandemics. Milan Brahmbhatt, a lead economist with the World Bank’s East Asia and Pacific region has said that, curiously, the most immediate economic impact of a pandemic might arise not from actual deaths or any illness but from the uncoordinated efforts of private individuals to avoid becoming infected. Think of what happened in Hong Kong during the SARS outbreak of 2004. In the attempt to minimize face-to-face interactions, sectors like tourism, mass transportation, retail, hotels and restaurants, all took a big hit. The total loss in the East Asian regional GDP during the period was roughly around 2% even though about 800 people ultimately died from SARS. Yet, a 2% loss of global GDP during a global influenza pandemic would represent a loss of around $200 billion in one quarter (about $800 billion over a whole year)—an altogether more deleterious financial impact than the one caused by SARS.

And then there’s bioterrorism. Those in the defense sector are wary about the government’s policy of classifying bioterrorism in the same group as naturally occurring outbreaks, though it’s often a question of necessity and expediency when the same branches of health and human services that deals with salmonella has to deal with anthrax and small pox. There was even a mild, rather seemingly incredulous scare in 2010, when U.S. intelligence reports revealed that Al Qaeda operatives in the Arabian peninsula had planned to drop ricin and cyanide poisons in various buffet and salad bars across the country (the fans of Breaking Bad will know that after Season Five’s infamous ricin episode, that sort of approach is horrifyingly effective and easy).

The fact remains that more public health professionals and qualified epidemiologists need to be trained in global surveillance techniques that will help combat the spread of infectious diseases across borders. The epidemiologist superheroes recently embodied by Jennifer Ehle, Kate Winslet, and Marion Cotillard in Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 film Contagion are in some sense an accurate depiction of what adept disease surveillance professionals do, but there just aren’t enough of them to go around in the world given the demands put upon the healthcare sector by growing populations and increased travel.

So it was no surprise to Secretary of State Kerry’s audience that a necessary assurance and pledge from the government’s health branches to protect American lives came at the height of the winter flu season. As the transition for many to Obamacare begins and as more people become aware of evolving pathogens and diseases transmitted through cross-border travel and migration and the sad reality of anti-biotic resistance, the public craves some statement of guidance from their government relating to catastrophic health threats. Though the question will be ultimately be, is the government as prepared as their preparedness mantra promises?

Find more articles by Farisa here.

Related articles in the categories Health, North America, Terrorism