The world has entered a period of extreme stress, faced with challenges of globalisation, economic unpredictability, climate change, and resource scarcity. These challenges test peace and stability, and have created greater social disparities in many societies, sparking conflicts within and next to borders. Although external assistance and intervention in post-disaster and conflict situations have been able to stabilise the situations at hand, they have largely failed to address the root causes of conflict, and to empower local communities. Often left out of the planning and consultation stages are the populations that are directly affected in emergency conditions, and they have little influence over their environment when external actors enter the picture. More than ever is the world in need of people-centric approaches to peacebuilding and development. One piece of the puzzle lies in the community itself – the power of indigenous knowledge. The building on, and rediscovery of existing indigenous insights and resources can be a way to improve the understanding of a crisis situation and to create a sustainable peace.

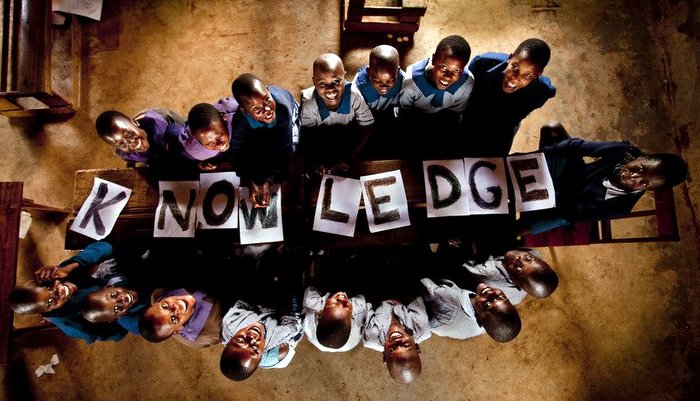

Indigenous Knowledge

Through the collection of experiences over time, societal relationships, a development of unique practices, and generational inheritance, the concept of indigenous knowledge is created. Indigenous knowledge is the in-depth understanding of a local environment, through the accumulation of knowledge over long periods of time, passed down, and eventually imbedded in a community’s way of life. It is separate from other types of knowledge because it originates inside a community, it is maintained by an informal network of passing on information, it is collectively owned, geographically specific, and it is malleable and able to adapt over time.

Indigenous knowledge has also been developed through the social construction of culture. Over time, cultures have been created through unique traditions and oral histories, and dowsed with influences from external forces, where a multi-faceted form of knowledge is created. Understanding a culture in a disaster, or conflict situation, is critical to addressing the root causes of a problem and to create an inclusive humanitarian operation. Promoting the use of traditional methods and practices to address the needs of local populations in crisis situations has shown that it strengthens cultural identity and promotes sustainable socio-economic development simultaneously. Culture should be seen as a positive force for developing indigenous styles of conflict resolution, instead of suggesting that it is a difficult feature which has to be incorporated into a Western-style model. Utilising indigenous knowledge at the decision-making level has great potential because knowledge, by nature, is ultimately adaptable for changing social relations and structures.

Indigenous Knowledge and Disaster Risk Reduction

Communities and societies have always had curve balls thrown at them by Mother Nature, and over long periods of time of learning from previous experiences, it has led to the development of strategies for surviving and coping. The appreciation of indigenous knowledge by the international community has remained primarily anecdotal. Western approaches to Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) have largely ignored the potential wisdom indigenous knowledge can offer in an emergency response situation, and also in regards to adapting new technologies in local environments. But even before high-tech communication capabilities, early warning systems, and operating procedures were created, local communities have been able to depend on traditional methodologies to reduce risks and respond appropriately. There are many lessons indigenous knowledge can provide in order to close the gap between Western scientific knowledge, and those of the locals.

Indigenous knowledge can strengthen DRR processes in a variety of ways. Firstly, incorporating indigenous knowledge into responses provides a core foundation to build upon, a foundation which by its nature, allows for flexibility in adding to an existing knowledge base. By using this foundation, it can also help avoid the notion of cultural invasion from external actors, because local solutions become tied in with technologically advanced management. Indigenous methodologies are already understandable to its users, and local knowledge provides specific information about a disaster-prone area to improve the implementation of projects. DRR approaches should also be based on the needs of the communities affected, which will empower locals to sustain a project that has been implemented, and allow for all-inclusive participation. Through empowerment and leadership, the practice of good governance is strengthened. Indigenous knowledge is also an effective educational tool to reinforce a culture of safety and resilience, and indigenous DRR approaches are beneficial because, although they are contextual, they can be transferred and applied to other communities in similar situations.

Farmers of Tuan Tu commune in An Hai, Ninh Phuoc who have applied intensive farming techniques on growing cassada trees have resulted in high economic productivity. (Photo: Duy Anh)

In 2002, indigenous methodologies were demonstrated when Tropical Cyclone Zoe lashed through the Solomon Islands, specifically hitting Tikopia and Anuta, two of the world’s smallest islands. When warning messages were unable to be transmitted because of severe weather damaging radio reception, traditional methods for risk reduction were employed. Runners went from hut to hut and to churches to inform the people of the impending disaster, in which preparations began immediately. Strong societal networks in the Solomon Islands with respect to customs and belief systems supported the initial resilience that was demonstrated during the cyclone period. The local population strengthened roofs with palm fronds and banana trunks; they gathered in communal huts; and built a sea-wall along the beach made out of coral, which was effective against the storm. Most people felt well protected in traditional huts built with low walls and sloping thatched roofs.

Less-developed areas such as the Ninh Thuan province of Vietnam have also shown the merits of using indigenous knowledge to reduce the risk of disaster situations. Ninh Thuan is the driest area in the country, and a commune on the coast, An Hai, has developed methods of weather forecasting using indigenous knowledge to dictate the cultivation of crops. The community’s livelihood is dependent on agriculture, and it is critical for them to predict drought seasons. As meteorological systems are not accessible, the people of An Hai observe the moon as well as the activities of dragonflies to figure out when the rain will come as well as timing the preparation and planting of seeds. These methods have been successfully passed down through oral histories, proverbs and folk songs, and are examples of strategies which can be disseminated to other communities in similar situations.

Indigenous Knowledge and Peacebuilding

Peacebuilding initiatives from external actors have neglected and dismissed community and local methodologies for conflict resolution. This is beginning to change by the growing recognition of the potential and power indigenous knowledge can have on influencing reconciliation. As previously noted, indigenous knowledge is no longer ‘pure’ – it is mixed with elements of colonialism, imperialism, globalisation and the like. Traditional customs are assimilated with new flavours, but it is still possible to pick out certain approaches which do not belong in institutions originating from the West. Even though peacebuilding methods are local in nature, and it is dangerous to apply a ‘one size fits all’ model to resolve conflicts, there are concepts which can transcend knowledge bases.

Firstly, indigenous notions of conflict transformation lie in the key aim of restoring relationships and community harmony. Conflict is not viewed as a fixed entity, but as a continual process where conflict can be used to develop new and positive relationships. Reconciliation is imperative, and re-integration of perpetrators is necessary to restore this harmony – punishment is not the main goal, which is why traditional methods tend to stream more into the concept of restorative justice. Secondly, indigenous knowledge casts aside the idea that social institutions are critical for building peace and stability – as in the midst of a conflict, resolution measures have to be applied in one way or another, which is where deep-rooted peace cultures in communities are revealed. Peacebuilding and reconstruction cannot be boxed into categories, as indigenous knowledge is holistic and has many facets that include social, economic, political, cultural, and spiritual areas. Finally, indigenous peacebuilding methods are inclusive and public. Communities listen and try and include all views in a society. This way, the process is centred back to the people, which create empowered societies to foster further change. Culture is not seen as not a problem, as typically noted by the West as a hurdle to building peace, but it is part of the solution.

Of course indigenous knowledge is not bulletproof, it has its own range of problems which need to be kept in mind. Certain methodologies may interfere with universal notions of human rights, knowledge application may be confined to a community level, and methodologies can take a long period of time to implement, be subject to distortion and abuse, and be patriarchal in nature. But creating a fusion of approaches to peacebuilding can nurture more sustainable and people-centric initiatives. Indigenous methodologies can be utilised in situations of chaos, they are inclusive and participatory, they focus on all parts of a conflict to include a psycho-social and spiritual element in societies, time and process become contextualised to the culture, and they can be largely accepted and seen as more legitimate because approaches are not focused on the state.

Florence „Dom-an“ Macagne Manegdeg and her morning ritual at the the Kasiyana Peace and Healing Center in Sagada. The mountains of Sagada have been a refuge for Manegdeg, whose husband was one of the hundreds of activists killed while Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was president. In 2010, Manegdeg turned her home in this farming village into a center for peace and healing, a respite for individuals who have experienced trauma and a center for those who are advocating and volunteering for peace and healing programs. (Photo by Mario Ignacio)

One example of the implementation of indigenous knowledge is during the difficult post EDSA Revolution in the 1980s and 1990s in the Philippines. The people of Sagada initiated a ‘peace zone’ which revived customary peacebuilding methodologies, asserted community rights, and protected the interests and welfare of the community. The zone was created as a mechanism for demilitarisation, and to initiate dialogue between sectoral, multi-sectoral, and community groups. The peace zone emphasised that civilian interests trumped those of the armed groups involved, and to respect and uphold democratic ideals. The Sagada Peace Zone has had a lasting significance and has aided the dismantling of a culture of war; promoted indigenous notions of empathy; built respect and solidarity among the community; promoted notions of human rights and responsibility; and nurtured indigenous spirituality.

The conflict in Bougainville, Papua New Guinea in the 1980s and 1990s, displays the example of an inclusive peace process. Stakeholders from all levels of society were included in the ceasefire agreements. As the participation of various parties in the conflict became blurred, it was critical that lower ranking individuals from the warring factions were obligated to the agreements made, and that civil society took a shared responsibility for the post-conflict situation. The opinions of chiefs, and elders of respective communities, and the role of women in local peacebuilding efforts were recognised as paramount to reaching a successful peace agreement.

The world is changing at an accelerated rate, and the environmental hazards are only increasing – the consequences for local communities, especially those belonging to small island states and less-developed regions, need to be addressed, and need to be addressed in a way that will fit with indigenous customs. In both DRR and peacebuilding strategies, it is important not to have an exclusive top-down approach, but to incorporate methodologies and knowledge from those directly affected for a collaborative effort in response to a crisis situation. Indigenous knowledge should be included in decision-making levels when creating projects in response to crisis situations, and for its importance to be recognised in international frameworks. By combining methodologies and empowering local communities to take charge of post-disaster and conflict situations, it strengthens their capacity to respond to future risks, and adds to the extensive knowledge base to be passed on to generations down the line.

This article was originally published by offiziere.ch

Also by Sandra

The Last Drop: Water as a Cause of Conflict?

The Last Drop: Water as a Cause of Conflict?

Global environmental change is increasingly challenging our surroundings. Through destructive weather events, water scarcity, food shortages and natural resource competition, we are being forced to alter our daily lives and adapt to the effects of the degradation of land and man-made creations. …

Terror on States or States of Terror?

Ask yourself this question: what are the first images that come to mind when you think of a terrorist? I was asked this question not too long ago and was shocked by the first pictures which flashed through my mind.

Women and Peacebuilding in the Asia-Pacific

Women and Peacebuilding in the Asia-Pacific

Military occupations, terrorist activities, organised crime – these are many of the top stories which we see daily in the media. But how often do we hear about non-violent movements, …