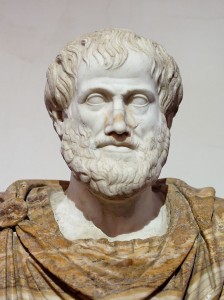

Aristotle, 384 – 322 BCE, was a Greek philosopher.His writings cover many subjects – including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theater, music, rhetoric, linguistics, politics and government – and constitute the first comprehensive system of Western philosophy. (Image: Wikimedia)

“So virtue is a purposive disposition, lying in a mean that is relative to us and determined by a rational principle, by that which a prudent man would use to determine it,” the Greek philosopher Aristotle once wrote. Curiously, many students now read Aristotle in more theoretical disciplines like philosophy. However, for Aristotle, the topics of virtue and prudence were key concepts in his practical science of politics. Aristotle classified prudence, or phronesis, as a virtue that involved considering actions and determining outcomes consistent with living well among others in the city, or polis.

In many ways, Aristotle’s understanding of prudence has deeply impacted how we think, write, and speak about contemporary foreign policy. Among international relations theorists like the LSE’s Chris Brown and the University of Sheffield’s David McCourt, Aristotle promoted a prudence that amounted to a kind of ethical know-how. Practicing Aristotelian prudence enables politicians and diplomats to become more aware of how foreign policy decisions impact what it means to “live well.”

In the 21st century, “living well” often involves making decisions that protect two interlocking ideas: national sovereignty and respect for human rights. Recently, these two ideas have converged onto a single doctrine, Responsibility to Protect, popularly known as “R2P.” This threshold norm, or fundamental principle, of contemporary international law holds that national sovereignty is not an inviolable right. Instead, sovereign states are responsible for protecting their peoples against human rights violations, like genocide and crimes against humanity. Where a sovereign state fails to uphold that responsibility, R2P devolves to the “international community,” encompassing a wide array of national governments and supranational institutions like the United Nations Security Council and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Take for example, President Obama’s response to the ongoing crisis in Syria. Speaking in September, Obama invoked the 1994 Rwanda genocide to illustrate the importance of R2P and the consequences of inaction against President Bashar al-Assad’s alleged use of chemical weapons on the Syrian people. “I think that the security of the world,” Obama stated, “and my more particular task of looking out for the security of the United States requires, that when there’s a breach this brazen of a norm this important, and the international community is paralyzed and frozen and doesn’t act, then that norm begins to unravel.” For Obama, upholding R2P in Syria was a matter of safeguarding both American security interests and enforcing the international commitment to human rights.

Yet, a large part of the Aristotelian story is missing. Academics and politicians labor over how the decision-making process may hinder or forward security and human rights interests at all levels of governance. Rarely, however, does anyone ask, “What happens next?” Consider, the Syria crisis began three years ago in March 2011. Negotiations have been ongoing and only climaxed with news of chemical weapons and mass atrocity. But when those negotiations end and the international community have taken action, when American and international security interests have been met, when the force of international human rights has come down on the Assad regime—what’s next? How does the international community or the Syrian people begin to transform the war-torn country into a state where individuals can “live well”?

For Aristotle, living well is not merely synonymous with establishing and actively pledging oneself to certain ideals like national sovereignty or human rights, but doing so with the distinct purpose of considering what the highest human good is and how it can be achieved. Recently political and legal theorists who call themselves “neo-Aristotelians” have constructed human development models that can, in many ways, fill in this part of the puzzle. Perhaps the most prominent neo-Aristotelian is University of Chicago law professor Martha Nussbaum, who has asked “What is each person actually able to do and be?” and “What real opportunities are available to them?” Nussbaum and her colleagues might not measure the prudence of a foreign policy decision on how effectively it achieves dominant national security or human rights interests, Instead, they might measure the prudence of a foreign policy decision based on how well it cultivates more intangible interests, like human dignity or human capability.

Operationalized in a hypothetical post-conflict Syria, the neo-Aristotelian development model might involve ensuring democratic elections that protect the rights of the individual or even forwarding the United Nations Millennium Development Goals that establish greater gender and socioeconomic equality. Yet, Nussbaum and neo-Aristotelians are also interested in identifying and coining how capabilities like “control over one’s environment” and “bodily integrity” might also be established. These capabilities encompass protecting individuals’ rights to political participation and security against state-sanctioned violence, in addition to commitments to environmental ethics, the cultivation of meaningful labor and professional relations, and respect for human autonomy and personal choice.

By and large, Aristotle’s practical science of politics opens the way for critiquing and augmenting contemporary decision-making in the foreign policy arena. From an Aristotelian standpoint, military interventions and the deployment of aid workers are purposeless if these actions do not also create the conditions for individuals to build and live in thriving polities. Although an aspirational, and perhaps even utopian, mode of assessing action and the pursuit of interest, an Aristotelian approach can imbue international relations with a deeper, more human purpose.

More articles in the categories History and Personalities

Also by Ani

Egypt: A 19th Century Answer to a 21st Century Question

If we are to evaluate the legitimacy of the current Egyptian government and project a political future for the country, we must turn to a new theoretical framework. Perhaps now, more than ever, the reflections of the 19th century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche are timely.