Internecine violence continues to embroil Iraq and that violence more often than not is along the fault lines of religious and ethnic groups. In a previous post, I argued that in situations of insecurity and uncertainty individuals will more closely identify with one group than with another group. To take that argument further, I turn now to a discussion of some of the major decisions that took place after the 2003 invasion and how these decisions contributed to the violence. The weak state apparatus of the Iraqi state leading up to and after the 2003 invasion was a contributing factor to the sectarian violence. In Iraq, a weak state apparatus and the inability of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) to fill the gap led to the proliferation of sectarian violence.

Following the March 2003 invasion, a De-Baathification Commission was established to purge high-ranking officials associated with the former regime. As a part of that strategy, Bremer disbanded the Iraqi army and emphasized that the army was a symbol of the previous regime. As Colin Powell later said, the CPA should have worked to weed out those who had been “Saddemites” while at the same time preserving the existing infrastructure of the army. After the announcement, thousands of former Iraqi officers took to the streets in protest. One former officer who was interviewed said that “if they [the Coalition authorities] don’t pay us, we’ll start problems. We have guns at home. If they don’t pay us, if they make our children suffer, they’ll hear from us”. Suffice to say, the decision to disband the army has been credited with contributing to the instability after 2003. By disbanding the Iraqi army, the CPA ostracized some members of the populace who became more inclined to take up arms against the state.

The weakness of the Iraqi state was also evinced by the destruction of state infrastructure. First, the First Gulf War and the international sanctions that followed crippled the Iraqi state and economy. Second, the immediate aftermath of the 2003 invasion wrought additional havoc upon the Iraqi state. Mass looting took place in April of that year, and 17 of 23 of government buildings for central ministries were destroyed. Third, the De-Baathification Commission did not just target the armed forces but the civil service as well. State civilian institutions therefore suffered a massive loss of “institutional memory,” making it difficult for the state to deliver basic services to ordinary Iraqis.

The pursuit of democratization also contributed to the emergence of sectarianism. This is not because democratization is necessarily problematic in heterogeneous or post-conflict societies. Instead, the ordering sequence affects the likelihood of internecine intrastate conflict. Why is this so? When state institutions are weak, political elites are incentivized to use nationalist rhetoric to succeed in elections. Together, the weakness of the Iraqi state and its rapid democratization fueled sectarian violence. Larry Diamond, who advised the CPA on democratic reforms in Iraq, has said that it was a mistake to hold national elections so soon after the invasion. In his own words: “ill-timed or ill-prepared elections do not produce a democracy.”

At the same time, some scholars and policy makers, such as Paul Collier as well as Rory Stewart, warn that a process of delayed democratization can lose momentum and increase the renewal of conflict. In a TED talk, British Member of Parliament Rory Stewart argues that the “delayed” approach was untenable in Iraq:

“We [the Coalitional Provisional Authority] went through a period of feeling that we should delay democracy, that the lessons learned from Bosnia [is] that elections held too early [result in extremism]…let’s not have elections for 2 years. Let’s invest in voter education…The result was… a huge crowd of people standing outside my office screaming for the election. I said: “What’s wrong with the people we chose?” The answer came: “The problem isn’t the people you chose. The problem is that you chose them.”

While rapid democratization in Iraq contributed to the escalation of sectarianism in Iraq, a gradual transition could have contributed to the escalation of sectarianism.

To recap, the Iraqi state could not make credible guarantees for its citizens. Many Iraqis suddenly found themselves out of a job or without clout as a result of the De-Baathification process. A fundamental problem of the new regime was not only that it failed to provide security to a large number of its citizens but that it was based on a process of exclusion. During the January 2005 elections voter turnout was ominously low among the Sunni population, with a 2% turnout in the Sunni-dominated governorate of Anbar. The main Sunni Arab political party boycotted the elections arguing that a large number of Sunni Arabs had not been adequately educated about the election and that the growing violence in the communities north-west of Baghdad made it impossible for elections in that area to be genuinely free and fair.

The newly elected representatives agreed that a permanent constitution would need to be drafted by August 15th, 2005 and put to a referendum by October 15th, 2005. A number of scholars and policy-makers have argued that the constitutional drafting process in Iraq proceeded too quickly and that it served to fuel sectarian tensions. Sunni Arabs representatives were by and large opposed to the constitutional provision that would allow any of the 18 governorates to join together to form regions. The draft constitution also recognized the authority of the Kurdish Regional Government (Article 113). For Sunni Arabs, these provisions would mean the condemnation of the Sunni Arab community to ignominy: presumably, Shi’ite dominated governorates of the oil-rich south could join together and exercise considerable clout in the new political regime; meanwhile, Sunni Arab communities, such as those in Anbar, would be bereft of oil wealth.

The draft constitution also included such provisions as 2007 deadline to hold a referendum on the status of the oil-rich governorate Kirkuk. Specifically, representatives wondered, was that governorate to come under the jurisdiction of the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG)? Three governorates currently fall under the jurisdiction of the KRG, yet the KRG exercises de facto control farther south than official borders demarcate. The governorate of Kirkuk is officially outside the jurisdiction of the KRG but it has been a source of contention since 2003.

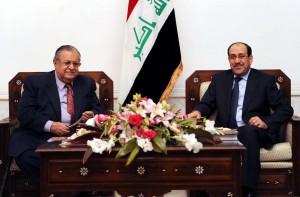

In 2008 the Iraqi parliament attempted to pass a bill regarding the status of Kirkuk (while no Kurds were present during the vote). Article 4 of the bill required that Kirkuk to be shared equally among major ethnic groups. President Jalal Talabani, himself a Kurd, used his veto power to prevent the bill from becoming law. The incident served to incense both Arabs and Kurds. Arab representatives accused the Kurds of pursuing narrow interests while Kurdish representatives felt they were not being treated as equal partners in the new regime.

The dispute over Kirkuk may have more to do with access to oil than with group identities. Yet group identities are the very least affected by such exclusionary regime practices—that is to say, an individual will more strongly identify with one group and less with a political regime if the individual perceives that political regime as acting against his or her interests. Kurdish identity has come to play a definitive role for those living in northern Iraq. It is not unreasonable to posit that for a national Iraqi identity to trump other group identities, Kurdish Iraqis will have to be convinced that they are equal partners in the Iraqi federation. Meanwhile, exclusionary regime practices have fueled sectarian tensions.

Sunni Arabs have likewise felt excluded from participation in the new regime. In January 2010, the Justice and Accountability Commission (successor to the De-Baathification Commission) invalidated 499 candidates in the lead-up to national elections. Prime Minister Al-Maliki publicly advocated for the disqualification of these candidates, warning of a “Ba’thist” threat, and it is possible that Maliki did so as a ploy to shore up the Shi’a vote. This is peculiar, given that the State of Law coalition was, at the time, ostensibly a secular, cross-sectarian coalition. Regardless, these turn of events reinforced the perception of Sunni Arabs that the new regime was conspiring against them and that it was working in the interests of the Shi’a.

As Harith al-Qarawee writes in The National Interest, Nouri Al-Maliki has been focused on achieving a monopoly on force without creating a sense of inclusion. If Al-Maliki hopes to legitimize his authority, he and other political elites will have to isolate extremists by building more inclusive institutions. Maliki now finds himself in a Catch-22. He can appeal to his electorate and support base by continuing to consolidate his power—he can continue to achieve a monopoly on force without inclusion. Yet to do so may lead Iraq down the path of civil war. To build more inclusive institutions, Iraqi leaders will have to focus on restructuring the political institutions of their country.

Federalism is an important concept for understanding Iraqi politics. The 2005 constitution describes Iraq as a federal state and the very word “federalism” is considered contentious for Iraqis. Some scholars maintain that ongoing civil unrest is best viewed as disagreement over the future of Iraq’s federal system, rather than as disagreement between sects. The apparent lack of consensus regarding Iraqi federal relations will have adverse effects on the longevity of this nascent regime. My future posts will therefore deal with federalism and its specific applicability to Iraq.

Also by Matthew

The origins of Sectarianism in Iraq

The origins of Sectarianism in Iraq

The internecine conflict that tore through Iraq in 2006-2008 may rekindle in the near future; the inflaming of sectarian tensions is a possibility.

Could restructuring the federal relations in Iraq create a lasting peace?

Could restructuring the federal relations in Iraq create a lasting peace?

The capacity of the Iraqi state is still tenuous and the sectarian tensions that embroiled the country after the invasion could re-emerge. Long-term stability for Iraq will require resolving disputes over federal relations.

Related articles in the categories Democracy, Middle East and North Africa

Trackbacks / Pings