In the last few weeks, the world media has reacted with shock at the clashes in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, which resulted in the ousting of President Mohammed Morsi and the installation of a military coalition in Egypt. Unable to believe that Egypt’s first democratically elected leader, who had replaced General Hosni Mubarak in 2011, had fallen to martial force, American President Barack Obama condemned the turnover. In a White House press release, President Obama called on the Egyptian government to cooperate with the people in order to “return full authority back to a democratically elected civilian government as soon as possible.” Similarly, Great Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron went so far as to declare that the British government had never supported military intervention, and demanded a “genuine democratic transition to take place” so that democracy could “flourish.”

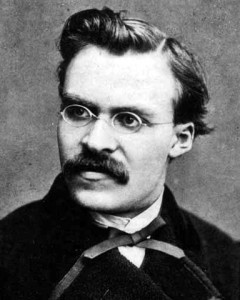

The statements of both President Obama and Prime Minister Cameron are not only hasty, but reveal the discursive limits of the Anglo-American liberal tradition. For these reasons, if we are to evaluate the legitimacy of the current Egyptian government and project a political future for the country, we must now turn to a new theoretical framework. Perhaps now, more than ever, the reflections of the 19th century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche are timely. This is primarily the case, because Nietzsche delineated those discursive limits and, in the process, provided a means to overcome them.

In his 1887 essay collection The Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche devised his notion of perspectivism and destabilised the very foundation of Anglo-American liberalism: the utility principle. Nietzsche believed there were many perspectives from which truth-statements could be made. As such, no valuation of an object could be an absolute truth, and all valuations therefore had to be valid. He famously lodged perspectivism against the utility principle, which, for its division of the world into “good” and “evil” imposed a prejudicial system of universal morality on human action and obscured the achievements of the individual.

If Nietzsche were then to evaluate the reactions of President Obama and Prime Minister Cameron, he would arrive at two conclusions. Firstly, these leaders measure the legitimacy of the current Egyptian military coalition against the absolute value of deliberative democracy. In extolling this form of government as the foremost political good and condemning any military force, both President Obama and Prime Minister Cameron forget the potential of the Egyptian military to bringing long-term stability to the region. Nietzsche would therefore ask us to qualify governmental legitimacy on the basis of action—that is, the policy successes and failures of the Egyptian government—rather than an abstract notion of “good.”

In many ways, this task is impossible, because Egypt’s political future remains, as the American think-tank the Brookings Institution put it “#EgyptTBD.” However, when we look back on the last sixty years of Egyptian history, we can see the ways the policy efforts of successive military-led governments have shaped Egyptian politics today. Furthermore, based on such historical precedents, we can isolate the challenges that sort of politics must confront to achieve long-term stability in Egypt.

We can trace the beginnings of democratization in Egypt to the 1952 Revolution, led by Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Free Officers Movement. Until this point, argued historian M. Riad El-Ghonemy in The Political Economy of Rural Poverty, Egyptian politics was the “classic example of a coalition between domestic and foreign capitalists in the monopolization of asset ownership in the rural economy.” In other words, political elites and multinational corporations controlled the Egyptian Parliament and constituted a political order hardly answerable to the majority of the population—especially the peasant fellaheen. The anthropologist-turned-novelist Amitav Ghosh, in his book In An Antique Land, has described the conditions of fellaheen life as one of “chronic indebtedness and dependency” on landlords, who controlled exploited fellaheen labour on “personal fiefdoms.” Consequently, the fellaheen possessed neither a sense of belonging to the Egyptian state, nor any means of interest aggregation.

This situation changed in 1952, when Colonel Nasser ushered in an era of policy reforms, which forged a social contract between the fellaheen and the government, and paved the way for later democratization efforts. Colonel Nasser instituted the Land Reforms of 1952, which may have restricted land ownership, but alleviated some of the pressing socio-economic inequality between the political elites and the fellaheen. In doing so, Nasser endowed the fellaheen with political agency by reining back the source of the elites’ power: land. Nasser’s reforms entitled families to land ownership, established farm cooperatives with access to agricultural technology, and established a minimum wage. These measures encouraged loyalty to the government and generated participation within state institutions, making popular politics a possibility.

Colonel Nasser’s reforms were curtailed by the succeeding government under President Anwar Sadat. However, these reforms provided the necessary conditions to establish a more democratic political order, which was increasingly inclusive of opposing interest groups. Thus, President Sadat’s 1971 Constitution solidified Egypt’s centrally planned economy in “accordance with the principles of social justice…and raising the standard of living.” More importantly, the 1971 Constitution established a multi-party system.

Yet, for all their successes, we can also see their failures in the demands of Tahrir Square protesters —both in 2011 and today. While Colonel Nasser and President Sadat certainly created a more democratic Egypt, it also suppressed—indeed, oppressed—the more populist opposition groups, such as the Muslim Brotherhood and the Tamarod. By the end of General Mubarak’s twenty-nine-year presidency, Time Magazine reported in 2011, Egypt’s opposition parties had been “stewing for so long” under “the stranglehold of Mubarak’s regime,” that the Arab Spring was in many ways inevitable. So in 2012 when newly-inaugurated President Mohammed Morsi proclaimed, “You [the people] are the source of power and legitimacy. There is no person, party, institution, or authority over or above the will of the people,” he not only recognized the efforts of preceding governments, but also acknowledged their shortcomings. Shortcomings, Morsi himself, accused of “’Brotherhoodization’ of the government”, was unable to overcome.

This historical framework allows us to look on Tahrir Square and isolate two areas, which the current government must address in order to legitimate itself as “democratic.” The military-appointed President Adly Mahmoud Mansour must mediate the increasing distances between the urban and rural, the secular and religious. In the last two years, political instability has driven out foreign investment, heightened the economic crisis, and contributed to socio-economic inequality. To make matters worse, the news agency Reuters has reported Egypt now faces the “longest absence [of imported wheat] from the market in years.” Needless to say, these developments will be weighing heavily on Egyptians’ minds, as many observe the holy month of Ramadan by fasting. The Egyptian people will therefore be looking to the government not so much for rapid democratic transition, as President Obama and Prime Minister Cameron would like to believe, but rather effective policies which can confront these challenges. Consequently, we must keep in perspective, in the spirit of Friedrich Nietzsche, the reality that the proof will be in the efficacy of policies, not in the form of the government.

[yop_poll id=”7″]

Related articles in the categories Democracy, History, Middle East and North Africa, Theories

Trackbacks / Pings