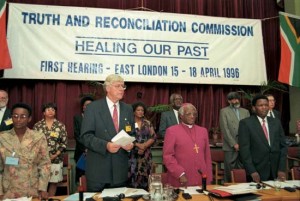

South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission with its Chairman, Desmond Tutu (Source: Britannica)

The debate about the moral and legal implications of amnesties is probably as contested as no other topic in the field of conflict resolution. For academics the debate is first and foremost about legal and moral implications whereas war-torn societies debate about nothing less than the chances for peace and the dangers of war.

Transitional justice processes represent a period during which governments and civil society have to balance individual demands for justice with the wider need for reconciliation. Proponents argue that amnesties are a necessary evil in order to initiate the process of transitional justice. This is a viable argument as conflict parties might demand amnesties as a precondition to stop fighting. Opponents, on the other hand, argue that amnesties breach international law which requires states to prosecute international crimes, such as genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Furthermore, the lack of prosecution is argued to lead to an insufficient fulfilment of the need for justice of the victims which is considered as sine qua non for reconciliation. Evidently, making a decision between prolonged fighting and an amnesty for perpetrators who might have killed tens of thousands is a decision that places societies truly between a hard place and a rock. Therefore, not only the legality, but, and most importantly, also the morality and thus the value of amnesties as a tool of conflict resolution is highly controversial.

Moral implications

Following the military trials in Nuremberg and Tokyo after the Second World War, criminal justice was further developed as a response to systematic and widespread violations of human rights in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Turkey, Cambodia and South Africa. The latter approaches, however, added a restorative dimension to the retributive approaches exercised in post-war Germany and Japan. Notwithstanding that amnesties were increasingly considered as tools to foster peace, their value became increasingly questioned.

The concept of amnesty lacks a widely acknowledged definition as most of the definitions fail to encompass the wide range of factors that are considered by amnesty laws, such as the type of crimes for which amnesty is granted, the individuals benefiting from amnesty laws and the circumstances which lead to the granting of amnesties.

Oftentimes amnesties are granted in order to end conflicts, or out of fear that prosecutions or the mere threat of prosecutions might be followed by violence; the examples of South Africa and Sierra Leone are cases in point where amnesty laws were the result of negotiation processes. In the case of the former, it was acknowledged that the possibility of an amnesty for the perpetrators of the apartheid regime was likely to support the peaceful transition to democracy. In the case of the latter, amnesties were considered the only option to halt the continued fighting of the Revolutionary United Front, the belligerents of a war that had already lasted eight years and cost the lives of 75,000 people.

Amnesties might also be granted due to pragmatic considerations. If large-scale crimes, such as the Rwandan Genocide, have been committed, the investigation and prosecution of every single case would present an insurmountable task for a pure retributive justice system. The economic and social effects that would accompany the imprisonment of large parts of the population would also render mass imprisonment impractical to say the least. Moreover, the few resources available might be required elsewhere to rebuild the country. Consequently, the willingness to grant amnesties is usually not manifested in philanthropic motivations, but rather in the necessity of avoiding further conflict and to use limited resources efficiently.

For an amnesty to be considered as legitimate it needs to be embedded into a wider reconciliation process, involving the political elites of all parties, the wider civil society and, most importantly, victims and perpetrators. Victims need to be given the opportunity to address perpetrators directly, and in order to ensure at least a minimal degree of accountability, perpetrators should provide the truth and offer a genuine apology reflecting on the crimes committed. However, individuals who bear the most responsibility shall be excluded from any amnesty provision. Reparations for victims, usually in monetary terms, need to be included also.

Transitional justice – a balance act between retributive and restorative justice (Source: Mama Quilla)

The value of amnesties cannot be assessed without considering the value of prosecutions. The exercising of justice is considered as a reward in exchange for the cost or harm endured by the victim. Prosecution, then, is claimed to provide victims with the fulfilment of the need for justice which often represents the start of the healing process. The Economic and Social Council, Commission on Human Rights of the UN (2005) stated:

“there can be no just and lasting reconciliation unless the need for justice is effectively satisfied”.

In addition, prosecutions underline the perpetrators’ guilt and remove them from influential posts in society. Trials are also hoped to serve as a deterrent and underline the responsibility of individuals which prevents the establishment of a culture of collective guilt that could lead to reprisals. Nonetheless, history has shown that the effect of deterrence is rather based on hope than on a guarantee. The Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials, for example, did not deter the individuals who are responsible for mass atrocities in Cambodia, Rwanda or Bosnia.

For states to opt for amnesties there must be hope that the eradication of the objectives and effects of retributive justice will be outweighed or at least meet by the objectives of amnesty, namely transition, peace, reconciliation, forgiveness and truth. The cause of heated debates becomes apparent when one questions the ability of amnesties to meet its aforementioned objectives. A violent conflict might be halted, but the long-term consequences need to be considered also. Whereas amnesties might establish short-term peace, punishments are hoped to establish peace on a long-term basis through the rule of law. Thus, retributive justice and amnesty both have peace as an objective, but the means to achieve peace are in stark contrast.

The difficulty of balancing amnesty and the need for justice led to a debate known as the truth v. justice or peace v. justice debate. Such a debate on the national level has global ramifications. National amnesty laws may foster positive peace and reconciliation. On a global level, however, these amnesties signal to individuals who have committed or plan to commit international crimes that they can hope for impunity. The naming of this debate implies that truth/peace and justice are mutually exclusive, but a truth-telling process might satisfy the need for justice as well. Such a process is likely to be encouraged if the perpetrator can hope for an amnesty in return for providing a true account of the crimes committed and the underlying motivations. However, relatives of victims are likely to demand retribution and the truth. Again, a situation that can only be compared to being between a hard place and a rock as perpetrators are less likely to provide the truth without an amnesty in return.

Legal implications

Since the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials, international criminal law is manifested in a growing body of treaties and laws which oblige states to investigate and, if necessary, prosecute criminals accused of international crimes or to extradite them. These include the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and the Geneva Conventions. If we define international law as the manifestation of the global society’s interests, values and standards, then any deviance ought to be condemned. Thus, states that weigh up the options of prosecution and amnesty do not only have to consider possible internal consequences, but are also required to assess obligations rooted in international law to investigate and prosecute individuals accused of international crimes. The International Law Commission stated that if an act by a state is considered as lawful based on its domestic law, it may still be considered as unlawful by the standards applied by international law. This underlines the illegality of national amnesty laws when confronted with international law that requires the prosecution of international crimes. Notwithstanding the fact that other treaties do not prohibit amnesties, it becomes evident, from a legal perspective, that amnesties are not considered to be a tool of conflict resolution. At this point it has to be emphasized that the Geneva Convention allows for amnesties for individuals who took part in hostilities in order to foster reconciliation. However, individuals who violated international law are to be excluded from amnesty laws.

The willingness of the international community to hold criminals accused of international crimes accountable was further underlined by the establishment of regional human rights courts in Africa, America and Europe as well as the International Criminal Courts for Yugoslavia and Rwanda and the subsequent International Criminal Court (ICC). Former UN General Secretary Annan (1999), stated at the opening plenary of the Preparatory Mission of the ICC:

“It [The ICC] puts the world on notice that crimes against humanity, which have disfigured and disgraced this century, will not go unpunished in the next”.

Thus, the intentions stated in previous conventions were now supported by institutions whose objectives it is to turn the end of impunity from a mere wish into reality.

The Lomé Peace Accord – Amnesty in return for peace was promised. Nonetheless, the war continued. (Source: BBC)

Although the willingness of states to end impunity is emphasized by treaty law and the establishment of regional courts and the ICC, there have also been cases in which state practice values the granting of amnesties as a tool of conflict resolution. Two prominent examples are the cases of South Africa and Sierra Leone.

In addition to states, treaty based organisations, such as the ICC have also considered the possible value of amnesties. The drafting process of the Rome Statute which was to set up the ICC indicated that theoretical questions about amnesties had to be answered for practical purposes. On the one hand, even delegations that were in favour of prosecutions were cautious of developing a norm that provides no flexibility for restorative justice approaches. On the other hand, it was feared that any exceptions might be misused and therefore contradict the raison d’etre of the ICC. In the end, the delegations were unable to agree on whether to incorporate an option for amnesty. The obligation to prosecute might, however, be fulfiled by the work of a truth commission rather than a court. The Prosecutor of the ICC might consider a national restorative justice approach as sufficient to satisfy Article 17(1)(b) of the Rome Statue which emphasizes the complementary regime of the ICC. That is, the ICC will declare the case as inadmissible if the respective state is willing and capable of investigating the case and, if necessary, to exercise justice. For this approach to be valid, the Prosecutor would have to decide that the commission did genuinely investigate the case, and decided not to prosecute in favour of an amnesty integrated into a wider reconciliation process. As a consequence, amnesties could be tolerated by the ICC.

The discussion during the drafting of the Rome Statute underlines that not only governments, but also international institutions are aware of the possible value of amnesties as a tool of conflict resolution. The legal and moral dilemma, however, can be addressed by granting an amnesty on the national level that is invalid on the international level. Thus, international courts or courts of other nations would be able to exercise justice.

The international community approaches national amnesty laws with caution and rightly so. After all justice and the rule of law provide the very pillars our societies rest upon. But conflict-ridden societies might face a decision between prolonged conflict and amnesty which requires a fine balancing act – an act which outsiders are unlikely to be to be able to gauge. The moral justification of amnesties is difficult to assess as morals change from one spatial or temporal context to another. Indeed, diverging moral values might even be found in the same society, among friends or family members. While international law is expected to be upheld, the reality on the ground is sometimes better served by deviant approaches. That is why international law offers room, albeit in limited form, for less rigid approaches. It is safe to assume that conflict-ridden societies know best what to do to pacify their country, and thus case-by-case decisions, rather than universal one-size-fits all approaches, are most likely to succeed.

[yop_poll id=”6″]

Related articles in the categories International Law, Peace Negotiations and Reconciliation

Dead is dead. If amnesties can stop the killing they are justified whatever the lawyers sitting in offices in New York or the Hague think. It is a motherhood statement to say “There can be no just and lasting reconcilliation unless the need for justice is effectively satisfied”. People’s need for retributive justice varies from culture to culture (and person to person). Think Mozambique. Life is not black and white, victims and perpetrators. Former child soldiers are usually both victims and perpetrators. It is a neo-colonialist Western imposition to tell Africans or Cambodians that they cannot agree to shut the door and forget the past whether they can forgive it or not.