Historical change is a curious phenomenon. Sometimes it occurs at a snail’s pace with years, decades elapsing before a crumbling autocracy finally gives way to a nascent democracy. Ask the people of Syria for example, as Human Rights Watch have done, how they perceive history to be unfolding before them. And they will tell you that history is “stuck”, “suffocating them” as a three year civil war that has consumed 130,000 people continues to reap havoc on a nation with no sign of political resolution. But historical change can also be abrupt, intense, unexpected. In less than forty eight hours, a seemingly resolute executive can collapse, forced to flee its sites of power with only a trail of burning documents left in its wake. It happened in the GDR. It happened in Romania. And now its happening in Ukraine.

Historical change is a curious phenomenon. Sometimes it occurs at a snail’s pace with years, decades elapsing before a crumbling autocracy finally gives way to a nascent democracy. Ask the people of Syria for example, as Human Rights Watch have done, how they perceive history to be unfolding before them. And they will tell you that history is “stuck”, “suffocating them” as a three year civil war that has consumed 130,000 people continues to reap havoc on a nation with no sign of political resolution. But historical change can also be abrupt, intense, unexpected. In less than forty eight hours, a seemingly resolute executive can collapse, forced to flee its sites of power with only a trail of burning documents left in its wake. It happened in the GDR. It happened in Romania. And now its happening in Ukraine.In the past week Ukraine has undergone what the historian Mark Kramer would call a period of “thickened history.” A period when a huge number of historically significant events, from the killing of eighty two protestors in Independence Square to President Yanukovitch’s removal from power, have occurred in an extremely short period of time. History feels condensed, concentrated.

This is of course not the first time that we have seen such a period of thickened history in recent years. The Arab Spring changed the geopolitical map as well as our perception of the Middle East over a course of weeks. There, just like in 1989, history acted as a lightning rod, conducting political currents from country to another. In 1989 events in Hungary spilled into the GDR. Then the collapse of the Berlin Wall served as further inspiration for Polish revolutionaries. Poland rolled into Hungary which in turn rolled into Romania. And in the Middle East, the self-immolation of a street vendor was the trigger of a transnational revolution.

We all know by now the role that social media are playing in the revolutions of today. They thicken history by conducing revolutionary fervour and dissent from household to household. They produce narratives of change, spark social movements in days. They conjoin the individual and the universal, embedding the experience of each citizen within a larger political movement. One only needs to study the case of a Ukrainian medic who tweeted her own expected impending demise after being shot in the neck by government forces to see how individual stories become the paradigms of revolution. The thickening of Ukraine’s history can be appreciated by studying statistics compiled by the Social Media and Political Participation Lab at NYU on Twitter activity in the country during the last week.

The four days from February the 18th to the 21rd saw up to 30,000 tweets being sent per hour in the country that included the hashtag #Euromaidan in either English, Ukrainian or Russian. February the 21st saw 230,000 tweets sent in little more than 12 hours. And on February the 22nd, the day that Yanukovitch fled the capital, the number of tweets per hour hit the 40,000 mark. As in the space of just twenty-four hours a EU-brokered peace deal collapsed, the Rada removed the President, elected speaker Oleksandr Turchynov as Interim President, freed Yulia Tymoshenko and restored the 2004 Constitution, history certainly seemed on the march.

But is thickened history to be desired? Should we see in swift historical change the engine of progress?

It is tempting to be seduced by the exhiliration of change, the crashing down of the old order and the promise of the new. For idealists like myself, the thickening of history may seem like a real asset to the growth of democracy, providing a warning to all oppressive rulers that their rule can end overnight. But, upon reflection, I fear that thickened history is actually the biggest challenge to the emergence of a successful democratic tradition in Ukraine.

I write this because as I was watching the dramatic events unfold on television, the words of the Polish intellectual Adam Michnik came to mind. Writing shortly before the revolutions of 1989, Michnik suggested that the “the only thing worse than communism is what comes after.” Michnik did not in any way mean this as a defense of the communist system- he himself looked forward to the advent of democracy in his country- but rather was expressing his anxiety that revolutionaries across Eastern Europe did not have any coherent vision for a post-Communist order. Michnik celebrated the demise of Communism, but looking into the post-Communist future saw only a political abyss. Michnik was afraid that a civic tradition could not survive in this dark, that deprived of the oxygen of democratic discourse and insitutional planning, the light of change would be snuffed out.

In many ways Michnik was right, and one need only look to the political cronyism in Russia and Ukraine, as well as the ethnic conflict that emerged in Yugoslavia, to see that rapid, unstructured political change- while breathtaking- has its dangers. By unstructured I do not mean anarchic. Anybody watching the events unfold on t.v. is aware that the changing of the guard in Ukraine has taken place in a remarkably orderly fashion. Protestors who rebelled against riot police last friday are now guarding political institutions, while there has been remarkably little violence since Yanukovitch left Kiev. By unstructured I am referring not to a lack of practical organization on the ground but rather to the lack of a coherent vision for a post-Yanukovich era.

As any historian or political scientist worth their salt will tell you, there are two sides to a successful revolution: the destructive side as well as the constructive side. All revolutions have a destructive element: governments are replaced, symbols of the ancient regime are torn down- quite literally currently in the case of 32 statues of Lenin dismantled across Ukraine in the space of one day- and constitutions are shredded. But a successful revolution needs a sense of what comes next, a vision of civic society. Without a coherent sense of direction, revolutions descend into political, and often military, quagmires. The Arab Spring is testimony to this. The opposition in Syria remains fractured; in Egypt, a nation is split between military-centric nationalism and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Which brings us to Ukraine where current events are already echoing those of the Orange Revolution of 2004. Yanukovitch seems to be gone. But what is the new Ukrainian political narrative? At the moment one does not really exist. Yes, Vitaly Klitschko, Yulia Tymoshenko, Oley Tyanhybok and Arseniy Yatsenyuk all joined together to confront Yanukovich, but once the common enemy is gone what binds them together? A pro-European stance of course, but that is not enough to build a civic tradition in a country scarred by corruption, nepotism and authoritarianism. More worrisome is that the politics of the opposition has been unbelievably superficial. And this is where the central paradox of the Ukrainian revolution comes to the forefront. While events on the ground have been layered on thick in recent weeks, political planning has been remarkably thin. The Ukrainian opposition lacks any ideological entrepreneurs, able to impose a narrative on Ukraine’s future. Instead, Ukraine’s opposition has ridden history rather than directed it. Yulia Tymoshenko was right when speaking in Independence Square on Saturday she declared to the people that “it is you, not the diplomats or politicians who have done this. It is not them, it is you.” Events have long overtaken Ukraine’s opposition. And they know it.

The superficial nature of Ukrainian political discourse is seen by examining the main contenders for the presidency. Klitschko’s party is called Punch, a name that embodies no vision of the future but refers solely to the fact that he is a former heavyweight boxer. Apart from claiming that he wants to clear out the elite- a central element of the discourse of destructive revolution- he has not posited a vision for change. Tymoshenko has rightly praised the heroes of Maidan square but how can she embody an alternative Ukraine when she was one of the elite who so abused power previously. By the limited nature of the applause she received on Saturday, it seems that the Ukrainian people concur. And Tyanhybok’s Svoboda or nationalist party have presented themselves as patriotic citizens who wish to root out corruption (again destructive revolution). All of which is great. But what next?

The superficial nature of Ukrainian political discourse is seen by examining the main contenders for the presidency. Klitschko’s party is called Punch, a name that embodies no vision of the future but refers solely to the fact that he is a former heavyweight boxer. Apart from claiming that he wants to clear out the elite- a central element of the discourse of destructive revolution- he has not posited a vision for change. Tymoshenko has rightly praised the heroes of Maidan square but how can she embody an alternative Ukraine when she was one of the elite who so abused power previously. By the limited nature of the applause she received on Saturday, it seems that the Ukrainian people concur. And Tyanhybok’s Svoboda or nationalist party have presented themselves as patriotic citizens who wish to root out corruption (again destructive revolution). All of which is great. But what next?

Which brings me to the questions of elections. This may seem heretical to those who like me believe in the democratic tradition but the Ukrainian parliament has made a mistake in pencilling in elections for late May. For me, such a date seems premature. Faced with such an aysmmetry between the intensity of events and the paucity of concrete political discourse, Ukraine needs time to let the dust settle and consider its next step forward. Its leaders need a number of months to establish their visions of a post-Yanukovitch order and to debate them in public. Before Ukraine can fulfill its democratic revolution, it must enact a discursive one. Solid, constructive political debate must replace populist denunciations of corruption, however true these may be.

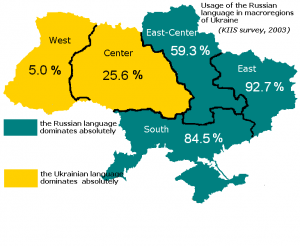

If this does not happen, the danger is that, given such a short turn around time to the next election, the quality of debate and political agendas will be sacrificed on the altar of identity politics. Even now it is becoming clear that Tymoshenko and Klitschko are operating more on the basis of their popularity (though in both cases limited) than the quality of their discourse. This is particularly worrying because the new government faces two problems to the East. The first of these are the 17.3% of ethnic Russians who reside in the South-East of Ukraine. The new order’s pro-European message is hardly winning appeal among a population with well known segregationist desires. Already, protesters in Sevastopol have established militias to resist the establishment of a new political order. A unified Kiev is needed in order to confront this challenge, otherwise ethnic Russians will gain greater encouragement and, possiblly, greater militancy.

And the second problem Ukraine faces is how to manage relations with Moscow. A fractured opposition leaves the danger that Vladimir Putin can play the game of divide and rule, striking a political bargain with one of its leaders in return for financial assistance or threatening to sponsor the dissent of these ethnic Russians if Kiev looks West to the E.U. Kiev will have the tricky task of negotiating a new relationship with Russia in the coming months- especially as the Russians will be seeking to guarantee the safety of their gas pipelines and their naval base at Sevastopol. Kiev cannot afford to enter this process divided.

One pattern seems to be emerging in history. Periods of remarkably thick history are being followed by periods of remarkably thin history. In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed in a period of days. But the years of cronyism, suffering and economic stagnation that followed have stretched out well into the current day. The Arab Spring induced a sense of euphoria, but as shown in Egypt and Syria, have given way to a cold, cold winter.

Unless Ukraine takes heed, I fear it will be next.

Also by Alexander

Welcome back to the Medieval World

Immanuel Kant wrote in the late 18th century that his was an age of enlightenment. If he were alive today it is likely that he would have to adjust his epithet slightly. For according to political theorists and international media alike we now live in a new age: the age of cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism is the new buzzword in international relations.

Related articles in the categories Democracy, Europe, History

Forgot how good a writer you are. I thought some famous professor wrote it.