Japan’s population is forecasted to decline from its current level of 126.66 million to between 92.03 and 100.59 million people by 2050.

Nearly a year has passed since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was elected with much europium in the 2012 general election. Upon his re-election, PM Abe introduced a series of reforms, dubbed “Abenomics” to revitalise Japan’s faltering economy. Japan has remained in the doldrums since the bursting of its bubble economy in 1985. Abenomics stands on a platform of looser monetary policy; a mammoth fiscal stimulus and the devaluing of the Yen. These policies are bound as Keynesian styled packages of reform. This resulted in the central bank issuing an inflation target of 2%, and printing £1 trillion pounds to stimulate consumerism. Additionally the bank also agreed to purchase 50 trillion Yen of government bonds, in hopes of investing on projects that benefit education; scientific research; and agriculture. Yet, history tells us that Keynesian policies have failed to inject life into Japan’s dying economy.

Japan’s economic woes

Like previous attempts to solve Japan’s economic woes, Abenomics has somewhat failed to revitalise Japan’s economy. In September, the Minister of Finance released data that painted a worrisome picture for Japan. Japan recorded its fifteenth trade deficit, with its current deficit up 64% from 932 billion Yen. Thus, Japan’s rising deficit has caused a 25% depreciation of the Yen. This has been fuelled by the inflated demand of fuel imports, since the fallout of the Fukushima nuclear crisis. This explains why Japan grew by 0.9% in the past quarter. Yet Japan is still expected to grow some 3.8% GDP growth by the end of the year. On the surface, it seems Abenomics is having some success to revive Japanese economic fortunes. Yet, a deeper analysis into Japan’s finances highlights a worrisome problem.

If Abenomics fails, there is a worry that Japan may implode. With national debt standing at 240% of GDP, it has begun to bare a heavy weight on the shoulders of its citizens to continuing financing it. This is because Japan’s demographic problem, with its declining and aging population, is said to threaten the D’s- its debt, deficit and deflation. Over time, Japan’s diminishing population will reduce the pool of labour throwing the purchasing parity to finance government budgets and the national debt in disarray. If the population problem is not resolved, we could see a Japan succumbing to using its rusty begging bowls on international markets in the foreseeable future.

A rapidly shrinking Japan

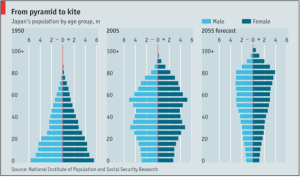

According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan’s population is forecasted to decline from its current level of 126.66 million to between 92.03 and 100.59 million people by 2050. This fall to Japan’s population can be attributed to the declining fertility rates, and outdated migration policies. Between 1945 and the 1970s, the number of children per woman dropped from 4.54 to below 2.1, the replacement level for a stable population. Today, Japan has a birth-rate of 1.29 children per women, which is one of the lowest figures globally.

Though migration could offset Japan’s declining population, its current policy contrasts to global concepts to replacement migration. Despite their desire to enter Japan’s labour market, many migrants are faced with high entry barriers. These include high levels of qualification, the requirements of adapting to Japanese culture and the difficulty of learning Japanese. As a result, migrants in Japan only represent 1.7% of the total population. Compared to rival OECD countries, 2.2 million migrants is a relatively paltry figure. As Japan’s migration policy reflects its mentality of solidarity, it is difficult to foresee any dramatic opening for migration into Japan. This subsequently led to the National Bureau of Research to predict Japan’s labour force to decline by thirty percent within three decades. Hence, it can be said that Japan’s policymakers will need to reassess traditional sentiments of closed solidarity, in order to prevent its demography in seriously hampering its attempts to economic revival.

Over time, Japan’s diminishing population will reduce the pool of labour throwing the purchasing parity to finance government budgets and the national debt in disarray. (Image: Telegraph)

Japan’s impending collapse

Compounded to its declining population, Japan’s population is also ageing rapidly. Average life expectancy amongst men stands at 79 years and women at 86 years old. This is worrying, especially as Japanese aged over 80, will increase from 5 million to 17 million by 2050. This has left Japan to be dubbed with the world’s oldest national population. An aging population impedes economic development as the government is required to allocate greater resources on social welfare rather than for development. According to the OECD, in 2010 Japan spent 22.3% of GDP on welfare, pensions and healthcare. Though this level mirrors rivals including the U.S and UK’s welfare spend of 19.8% and 23.8% of GDP respectively, Japan’s welfare bill will rise as its population continues age.

With Japan predicted to have a ratio of 1:2 for the proportion of retirees to those of working age, Japan’s economy is on the verge of collapse. Time is running out for Japanese citizens to continue paying for their retirement funds. The heavy load of the 2.4 trillion debts will be too large for the dwindling working proportion to continue maintaining. In order for Prime Minister Abe and policy makers to solve this looming problem, they will need to delve deeper into the fabric of Japanese society. Understanding Japan’s modern and unique society may hold the key in solving its economic and demographic woes.

A recent BBC documentary, ‘No Sex please, We’re Japanese’ by Anita Conway unpacked how Japanese society has come to exacerbate negative population growth. By analysing modern Japanese cultural trends, Conway found a consistent correlation to the number of young Japanese refraining from having sex. For example, the rise of anime culture has left young men acting out their teenage years at the expense of intimacy with the opposite sex. As a result, some males prefer a relationship with a virtual girlfriend rather than one in reality that often comes with responsibility. In comparison, Japanese females do seek relationships, but are limited in their choice of desired partners who fulfil their expectations. Additionally, with Japanese women now adhering to a working regime, they find less time to bear children, putting off child birth till their 40s. Thus, a 2013 survey conducted by the Japan Family Planning Association (JFPA), found 45% of women aged between 16 and 24 were not interested in having sexual liaisons. This has been compounded by the number of young Japanese remaining single until their mid forties. Since 2003, the numbers of singletons living at home aged between 35 and 44 increased from 1.91 million to 3.05 million in 2012. Thus the desire to refrain from sexual relations has left Japan with the inability to stem the decline in population levels as well as reviving economic fortunes.

Today, populations are viewed to be a pivotal resource for a country’s economy to grow. Yet, a population can also hamper economic progress. The root of the problem is deeply ingrained into Japanese society and is attributed to the phenomena called ‘Hikiomori’. Defined as ‘pulling away’ in Japanese, Hikiomori has come to describe the growing number of Japanese who have shunned the outside world in order to live as recluses. This phenomenon is greatly concentrated amongst young teenagers aged around 15, and is triggered by traumatic sources that stem from sekentei and amae. Sekentei refers to a person’s reputation within the community whilst Anmae revolves around the notions of independence. Thus, deteriorating economic prospects added with demanding social expectations have over burdened young Japanese to escape the grim realities that they are faced with. According to a 2010 Japanese Cabinet Office report, there are between 700,000 and 1 million sufferers diagnosed with Hikiomori. Though this is a rough estimate, it is a clear indicator for the potential impact it has on Japan’s labour force, and its ability to continue sustaining a faltering economy.

Though there are short term solutions that President Abe has at his disposal, any long term economic solutions will require dealing with reviving population growth, and in turn Japanese culture. For example, if Japanese policymakers were to alter current immigration policy, by relaxing regulations for long term migrants, there would be a welcome boost to both Japan’s population and its productive economic potential. Yet traditional deep rooted values have come to hinder Japan’s ability to solve its demographic problems and fix its economy. For the time being, it can be said that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will need to come to terms with the growing Hikiomori epidemic to enable Japan to reverse its current trajectory to economic growth. Predicting the future is difficult at best. However, present and past indicators show that the world may witness a weaker, more lethargic Japan clinging towards the upper echelons of the economic food chain.

Other articles by Akash Patel

Despite its economic success, is the future for China a bleak one?

Despite its economic success, is the future for China a bleak one?

Since the coining of the BRIC acronym in 2001, there has been great emphasis placed on the rising economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China…

Other articles in the categories Asia and Australasia, Economy and Trade

Trackbacks / Pings